Biomechanics/Neuromuscular

(7) RELATING THE COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP, BROAD JUMP, AND FLYING-10 YARD SPRINT TO FASTBALL VELOCITIES OF NCAA DIII PITCHERS

Braden A. Thorn (he/him/his)

Undergraduate Student

Linfield University

Tempe, Arizona, United States

Cisco Reyes, PhD

Associate Professor

Linfield University

McMinnville, Oregon, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

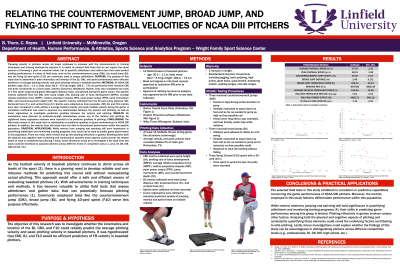

Throwing velocity in pitchers across all levels continues to increase with the advancements in training techniques and training methods for pitchers. It is useful to conduct field tests that do not require the same exertion of throwing a pitch at maximal intent, but to quantify athleticism and collect data that could predict pitching performance. A variety of field tests, such as the countermovement jump (CMJ), the broad jump (BJ), and the flying 10-yard sprint (F10) are commonly used to assess athleticism.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to determine if both kinematics and kinetics of the BJ, CMJ, and sprint performance were effective predictors of average pitching velocity and peak pitching velocity in baseball pitchers.

Methods: 14 NCAA DIII pitchers (age: 20.2 ± 1.1 yr, body mass: 82.2 ± 6.9 kg, height: 184.5 ± 7.6 cm) performed three maximal CMJ and three maximal BJ on a force plate. (Hawkin Dynamics; Westbrook, Maine). They also completed two trials of a F10 sprint using timing gates (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy), and pitched during live game action. The specific metrics collected from the CMJ were jump height (JH), braking rate of force development (BRFD), average relative propulsive force (ARPF), relative propulsive impulse (RPI), peak power output (PPO), jump momentum (MO), and countermovement depth (CD). The specific metrics collected from the BJ were distance (JD), horizontal force (Fx), and vertical force (Fz). Sprints were collected as time (seconds). CMJ, BJ, and F10 metrics were then correlated to each pitcher’s average fastball velocity and peak fastball velocity during the game. A correlation coefficient was used to examine any relationships between the metrics and pitching, as well as linear regressions to investigate predictive qualities between the metrics and pitching.

Results: No correlations were deemed as moderate-to-high relationships across any of the metrics and pitching. No significant linear regression analyses were reported to be predictor qualities of pitching.

Conclusions: The field tests chosen in this study had no relationship or predictive qualities to game performances in NCAA DIII pitchers. In addition, the metrics from this study were not able to discriminate performance within this specific population. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: While metrics from jumping and sprinting still have importance in quantifying athleticism and monitoring training programs, they could not be used to predict game performance in this population. There are many other factors that go into pitching effectively in games. Breaking down both the physical and cognitive side of pitching and continuing to quantify those aspects could uncover the deeper layers of what is considered top pitching. Finally, future directions would be to investigate if the data from this study could be beneficial to separate pitchers across different levels of competitive play (i.e. pros, DI, DII, DIII, high school, etc.)

Acknowledgements: None