Speed/Power Development

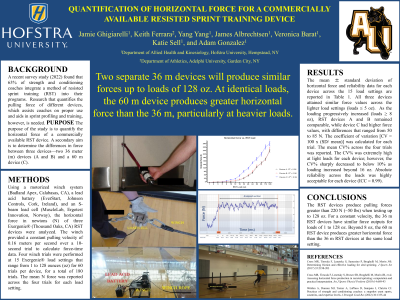

(44) QUANTIFICATION OF TENSILE FORCE FOR A COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE RESISTED SPRINT TRAINING DEVICE

Jamie J. Ghigiarelli, CSCS

Professor

Hofstra University

SMITHTOWN, New York, United States- KF

Keith Ferrara

Performance Coach

Adelphi University

Garden City, New York, United States - YY

Yang Yang

Graduate Student

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York, United States - JA

James Albrechtsen

Graduate Assistant

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York, United States - VB

Veronica Barat

Graduate Assistant

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York, United States

Katie M. Sell, PhD

Professor

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York, United States

Adam M. Gonzalez, PhD, CSCS *D

Associate Professor

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

A recent survey study found that 63% of strength and conditioning coaches integrate a method of resisted sprint training (RST) into their programs. These training methods, as reported in the literature, include parachutes, weighted vests, robotic tethered devices, and the most studied, weight sleds. Research that quantifies the pulling force of different devices, which assists coaches on proper use and aids in sprint profiling and training, however, is needed.

Purpose: The main aim of the study is to quantify the tensile force of a commercially available RST device. A secondary aim is to determine the differences in force between three devices—two 36-meter (m) devices (A and B) and a 60-m device (C).

Methods: Using a motorized winch system (Badland Apex, Calabasas, CA), a lead acid battery (EverStart, Johnson Controls, Cork, Ireland), and an S-beam load cell (MuscleLab, Ergotest Innovation, Norway), the tensile force in newtons (N) of three Exergenie® (Thousand Oaks, CA) RST devices were analyzed. The winch provided a constant pulling velocity of 0.16 meters per second over a 10-second trial to calculate force-time data. Four winch trials were performed at 15 Exergenie® load settings that range from 1 to 128 ounces (oz) for 60 trials per device, for a total of 180 trials. The mean N force was reported across the four trials for each load setting.

Results: The mean ± standard deviation of tensile force and reliability data for each device across the 15 load settings are reported in Table 1. All three devices attained similar force values across the lighter load settings (loads ≤ 5 oz). As the loading progressively increased (loads ≥ 8 oz), RST devices A and B remained comparable, while device C had higher force values, with differences that ranged from 50 to 85 N. The coefficient of variation [CV = 100 x (SD/ mean)] was calculated for each trial. The mean CV across the four trials was reported. The CV was extremely high at light loads for each device; however, the CV sharply decreased to below 10% as loading increased beyond 16 oz. Absolute reliability across the loads was highly acceptable for each device (ICC = 0.99).

Conclusions: The RST devices produce pulling forces greater than 220 N (~50 lbs) when testing up to 128 oz. For a constant velocity, the 36 m RST devices have similar force outputs for loads of 1 to 128 oz. Beyond 8 oz, the 60 m RST device produces greater tensile force than the 36 m RST devices at the same load setting. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: The results provide coaches and practitioners with a better understanding of the tensile forces produced by the RST devices. Two separate 36 m devices will produce similar forces up to loads of 128 oz. At the same load setting, the 60 m device produces greater force than the 36 m devices, particularly at heavier loads. Coaches must account for this difference when using the RST device for sprint training and program design.

Acknowledgements: "None"