Resistance Training/Periodization

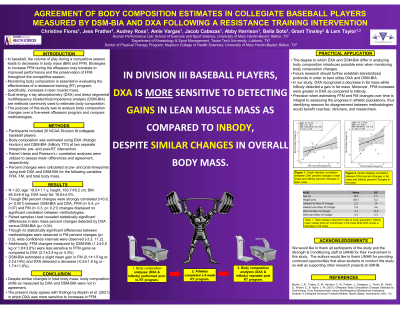

(23) AGREEMENT OF BODY COMPOSITION ESTIMATES IN COLLEGIATE BASEBALL PLAYERS MEASURED BY DSM-BIA AND DXA FOLLOWING A RESISTANCE TRAINING INTERVENTION

Christine Florez, MS, CISSN

Graduate Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Temple, Texas, United States

Jessica M. Prather, BS

Graduate Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States- AR

Audrey Ross

Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States - AV

Amie Vargas

Graduate Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States - jC

jacob Cabezas

Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States - AH

Abby Harrison

Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States - BS

Bella Soto

Graduate Research Assistant

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States

Grant M. Tinsley, PhD, CSCS,*D

Associate Professor

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States

Lem Taylor, PhD

Professor and Director of Graduate Studies

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

Belton, Texas, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Purpose: Body composition is comprised of fat-free mass (FFM) and fat mass (FM). In baseball, the volume of play during a competitive season leads to decreases in body mass (BM) and FFM. Strategies to increase FFM during the offseason may translate to improved performance and the preservation of FFM throughout the competitive season. Therefore, monitoring body composition is essential in evaluating the effectiveness of a resistance training (RT) program; specifically, increases in lean muscle mass. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and direct segmental multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis (DSM-BIA) are methodologies commonly used to estimate body composition. The purpose of this study was to analyze body composition changes over a five-week offseason program and compare methodologies.

Methods: 20 NCAA collegiate baseball players (mean ±SD; age: 19.5 ± 1.1 y; height: 183.7 ± 6.2 cm; BM: 84.5 ± 6.9 kg; DXA body fat: 16.8 ± 4.0 %) participated in this study. Body composition was estimated using DXA (Hologic Horizon) and DSM-BIA (InBody 770) at two separate timepoints: pre- and post-RT intervention. Paired t-tests and Pearson’s r correlation analyses were utilized to assess mean differences and agreement, respectively.

Results: Percent changes were calculated at pre- and post-timepoints using both DXA and DSM-BIA for the following variables: FFM, FM, and total body mass. Though BM percent changes were strongly correlated (r=0.9, p< 0.001) between DSM-BIA and DXA, FFM (r= 0.4, p= 0.07) and FM (r= 0.3, p= 0.21) changes displayed no significant correlation between methodologies. Paired samples t-test revealed statistically significant differences in lean mass percent changes detected by DXA versus DSM-BIA (p= 0.04). Though no statistically significant differences between methodologies were observed in FM percent changes (p= 0.3), wide confidence intervals were observed [-3.3, 11.2]. Additionally, FFM changes measured by DSM-BIA (1.2 ± 2.5 kg or 1.8 ± 3.6 %) were less sensitive to FFM gains as compared to DXA (2.7 ± 3.4 kg or 4.3%) while DSM-BIA estimated a slight mean gain in FM (0.1 ± 1.5 kg or 2.2± 14 %) and DXA detected a decrease (0.5 ± 1.8kg or 1.7 ± 11.9 %).

Conclusions: Despite similar changes in total body mass, body composition shifts as measured by DXA and DSM-BIA were not in agreement. PRACTICAL APPLICATION: The degree to which DXA and DSM-BIA differ in analyzing body composition introduces possible error when monitoring athletic progress. Future research should further establish standardized protocols in order to best utilize DXA and DSM-BIA. Additionally, the variance of FM changes measured by both methodologies should be explored. Precision when estimating FFM and FM changes over time is integral to assessing the progress of athletic populations, thus identifying reasons for disagreement between methodologies would benefit coaches, clinicians, and researchers.

Acknowledgements: None