Flexibility/Stretching

(54) EFFECT OF GENDER ON RANGE-OF-MOTION, HAMSTRING FLEXIBILITY, AND PERCEIVED LUMBOSACRAL PAIN IN NCAA DIVISION II COLLEGIATE ROWERS

Nicholas K. Carso, BS, CSCS

Student

Mercyhurst University Department of Sports Medicine

Andover, Connecticut, United States

Robert D. Chetlin, PhD, CSCS,*D, ACSM-EP

Associate Professor, Exercise Science Program Director

Mercyhurst University Department of Sports Medicine

Erie, Pennsylvania, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Rowers incur very high rates of chronic lumbosacral pain among athletic groups. This is likely due to repeated high intensity performance bouts, characterized by repetitive flexion & rotational loading. To our knowledge, no study has examined gender effects on upper & lower body range-of-motion (ROM), hamstring flexibility, & perceived pain in NCAA Division II collegiate rowers.

Purpose: To: (1) determine differences in upper & lower body ROM, hamstring flexibility, & various pain-related scales in male & female rowers, &; (2) examine potential outcome interactions by gender & rowing position (re: port vs. starboard).

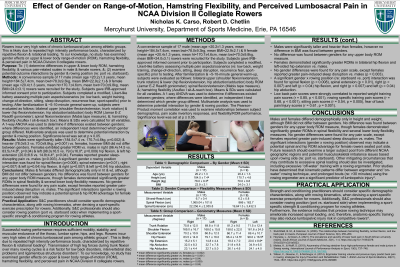

Methods: A convenience sample of 17 male (mean age =20.2±1.3 years, mean hheight=184.5±7.4cm, mean bwt=78.0±9.3kg, mean BMI=22.9±2.1) & 9 female (mean age =20.4±1.3 years, mean ht=170.7±4.6cm, mean bwt=70.0±9.8kg, mean BMI=24.0±3.1) rowers were recruited for the study. Subjects gave IRB-approved informed consent prior to participation. Subjects completed a modified, Likert-like battery assessing multiple pain aspects/scenarios (re: low back, weight training, change-of-direction, sitting, sleep disruption, recurrence fear, sport-specific) prior to testing. After familiarization & ~10-minute general warm-up, subjects were evaluated as follows: bilateral upper (shoulder flexion/extension, trunk rotation) & lower (hip flexion/extension, hip abduction/adduction) body ROM (Jamar E-Z Read® goniometer); spinal flexion/extension (Mabis tape measure), &; hamstring flexibility (Acuflex I sit-&-reach box). Means & SDs were calculated for all variables. A 1-way ANOVA was used to determine if differences existed between genders; where differences were identified, an independent t-test determined which gender group differed. Multivariate analysis was used to determine potential interaction by gender & rowing position. Significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results: Males were significantly taller (184.5±7.4 vs. 170.7±4.6kg, p=0.002) & heavier (78.0±9.3 vs. 70.0±9.8kg, p=0.001) vs. females, however BMI did not differ between genders. Females exhibited greater ROM vs. males in right (96.4±14.5 vs. 83.5±14.8º, p=0.04) & left (98.0±16.5 vs. 79.0±16.0º, p=0.009) hip flexion, & left hip extension (20.0±8.6 vs. 14.8±4.4º, p=0.04). Females reported greater sleep-disrupting pain vs. males (p=0.003). A significant gender x rowing position interaction was found for spinal flexion (p=0.008), spinal extension (p=0.01), right (p=0.007) & left (p=0.04) hip flexion, & right (p=0.007) & left (p=0.04) hip abduction.

Conclusions: Males & females differed demographically only in ht & wt, although BMI did not differ between genders. No difference was found between genders for any upper body ROM measure, though females demonstrated significantly greater ROMs in spinal flexibility & several lower body flexibility measures. No gender differences were found for any pain scale, except females reported greater pain-induced sleep disruption vs. males. The significant interactions (gender x rowing position) observed may indicate a potential spinal & hip ROM advantage for female rowers seated port side.

Practical Application: S&C practitioners should consider specific demographic characteristics, along with rowing kinematics, when devising a sport-specific exercise prescription for rowers. Additionally, S&C professionals should also consider rowing position (port vs. starboard) when implementing a sport-specific strength & conditioning program for rowing athletes.

Acknowledgements: The researchers would like to thank the Mercyhurst University Men's and Women's varsity rowing teams for their participation in this study.