Endurance Training/Cardiorespiratory

(52) THE EFFECTS OF PASSIVE HEAT EXPOSURE ON FIVE-KILOMETER RUNNING PERFORMANCE IN HOT ENVIRONMENTS FOR RECREATIONAL RUNNERS

Scott Flynn, MS

Faculty

Brigham Young University-Idaho

Idaho Falls, Idaho, United States- BJ

Baden Judd

undergraduate researcher

Brigham Young University-Idaho

Rexburg, Idaho, United States - AM

Ahnni Murat

undergraduate researcher

Brigham Young University-Idaho

Rexburg, Idaho, United States - DW

Danica Wilkins

undergraduate researcher

Brigham Young University-Idaho

Rexburg, Idaho, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Introduction: Numerous studies demonstrate both the health benefits and improved markers for exercise capacity with passive heat exposure to sauna and/or water immersion. Yet, there is limited research on whether these benefits translate over to increased running performance.

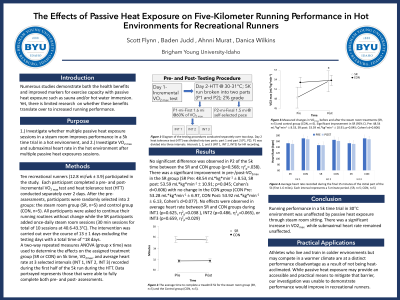

Purpose: 1.) Investigate whether multiple passive heat exposure sessions in a steam room improves performance in a 5k time trial in a hot environment. 2.) Investigate VO2max and submaximal heart rate alterations in the hot environment after multiple passive heat exposure sessions.

Methods: Twelve recreational runners, who ran similar weekly distances (12.8 mi ± 3.9) participated in the study. Participants completed an incremental VO2max test and a heat tolerance test (HTT) which were conducted separately over two consecutive days. The HTT consisted of a 5k running trial in a heat chamber set at 30-31°C (86-88°F) with the total distance being broken into two parts: part one (P1) was 1.6 miles at a pace eliciting 60% of their tested VO2max with a 2% incline followed by part two (P2) which was 1.5 miles at a self-selected pace with a 2% incline. The last 15 minutes of P1 was broken up into three, 5-minute time intervals in which average heart rate was recorded and labeled chronologically as INT1, INT2, and INT3. After completing the assessments, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a steam room group (SR, n=6) or the control group (CON, n=6). The SR participants completed once-daily, 30-min steam room sessions (total of 10 sessions) in temperatures of 40.6-43.3°C (105-110°F). All participants were instructed to continue their normal running routine with minimal changes while participating in the study. Following steam room sessions for the SR group, or a similar time period for the CON group, the follow-up testing was administered repeating the same procedure from the initial testing. For both CON and SR groups, the trial lasted ~18 days from pre- to post-testing. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA (group x time) was used to determine the effects on the assigned treatment group (SR or CON) on 5k time trial, VO2max, and average heart rate for the selected intervals.

Results: No significant difference was observed in P2 of the 5k time between the SR and CON group (p=0.568; η2p=.038). There was a significant improvement in pre-/post-VO2max in the SR group (SR Pre: 48.54 mL*kg*min-1 ± 8.53, SR post: 53.59 mL*kg*min-1 ± 10.91; p=0.045; Cohen’s d=0.606) with no change in the CON group (CON Pre: 53.28 mL*kg*min-1 ± 6.97, CON Post: 53.92 mL*kg*min-1 ± 6.13, Cohen’s d=0.077). No effects were observed in average heart rate between SR and CON groups during INT1 (p=0.625, η2p=0.038 ), INT2 (p=0.486, η2p=0.065), or INT3 (p=0.659, η2p=0.029).

Conclusion: Running performance in a 5k time trial in 30°C environment was unaffected by passive heat exposure through steam room sitting. There was a significant increase in VO2max while submaximal heart rate remained unaffected. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: Athletes who live and train in colder environments but may compete in a warmer climate are at a distinct performance disadvantage as a result of not being heat-acclimated. While passive heat exposure may provide an accessible and practical means to mitigate that barrier, our investigation was unable to demonstrate performance would improve in recreational runners.

Acknowledgements: None