Endurance Training/Cardiorespiratory

(36) INFLUENCE OF TRAINING VOLUME ON COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP CHARACTERISTICS IN DIVISION II CROSS-COUNTRY RUNNERS

Jacob Grazer, PhD, CSCS

Program Director: MS in Exercise Science

Kennesaw State University

Atlanta, Georgia, United States- MM

Mike Martino, PhD

Professor

Georgia College & State University

Milledgeville, Georgia, United States - SO

Shawn Olmstead

Assistant Coach

Flagler University

St. Augustine, Florida, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Countermovement jump (CMJ) assessments have been used over a multitude of sports to assess responses and adaptations to training stimuli. Along with the many reported benefits of distance running, there are several associated risks including overtraining and overuse injuries. These risks are associated with high training volumes, due to the repetitive forces on the lower body, along with other psychological and neuroendocrine factors. PURPSOSE: The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of training volume on lower-body power performance throughout a competitive cross-country season.

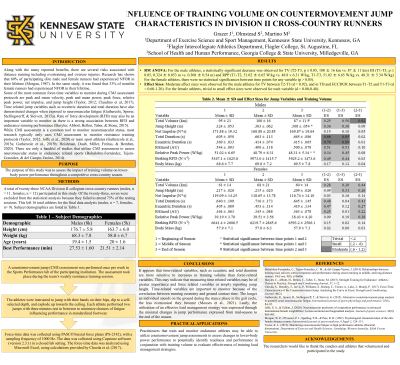

Methods: There were 16 athletes included in the final data analysis (males, n=7, females, n=9). A CMJ assessment was performed once per week prior to the team’s first weekly resistance training session following a standardized dynamic warm-up. The athletes performed two CMJs to a self-selected depth with their hands on their hips. Force-time data was collected using biaxial force plates at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. The data was collected and then subsequently analyzed using calculations provided by Chavda et al. (2017). Training volume data was collected by the coaching staff and shared with the principal investigator retrospectively. The season was divided into three time points: weeks 1-3 (T1), weeks 4-6 (T2), and 7-9 (T3). Using these time points, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on each of the following variables for males and females separately: Training volume (TV), jump height (JH), relative peak power (RPP), total duration (TD), eccentric duration (ECCDUR), net impulse (NI), reactive strength index-modified (RSImod), braking rate of force development (ECCRFD), and body mass (BM). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated to determine magnitude of differences.

Results: For the male athletes, a statistically significant decrease was observed for TV (T2-T3, p ≤ 0.05, 100 ± 16 km vs. 87 ± 11 km) JH (T1-T3, p ≤ 0.05, 0.324 ± 0.053 m vs. 0.308 ± 0.54 m) and RPP (T1-T2, 51.02 ± 6.65 W/kg vs. 48.8 v 6.31 W/kg, T1-T3, 51.02 ± 6.65 W/kg vs. 48.31 ± 5.34 W/kg) For the female athletes, there were no statistical significances between time points for any variable (p > 0.05). Moderate effect sizes were observed for the male athletes for TV between T2-T3 (d = 0.92), and in TD and ECCDUR between T1-T2 and T1-T3 (d = 0.60-1.20). For the female athletes, trivial to small effect sizes were observed for each variable (d = 0.00-0.48).

Conclusion: It appears that time-related variables, such as eccentric and total duration are more sensitive to increases in training volume than force-related variables. This may indicate that measuring time related variables may be of greater importance and force related variables or simply reporting jump height. Lastly, the utilization of an effective load management strategy was expressed through the minimal changes in jump performance expressed from mid-season to the end of the season. PRACTICAL APPLICATION: Practitioners that train and monitor endurance athletes may be able to utilize countermovement jump assessments to assess changes in lower-body power performance to potentially identify readiness and performance in conjunction with training volume to evaluate effectiveness of training load management strategies.

Acknowledgements: None