Biochemistry/Endocrinology

(43) STORING URINE SAMPLES WITH WATER BATH PRESERVES URINE HYDRATION MARKER STABILITY FOR UP TO 21 DAYS.

Nigel C. Jiwan, MS (he/him/his)

Doctoral Candidate

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States- CA

Casey Appell

Graduate Part-Time Instructor

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States

Marcos S. Keefe, MS CSCS

PhD Student

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States

Ryan A. Dunn, MS (he/him/his)

PhD Student

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States- YS

Yasuki Sekiguchi

Assistant Professor

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States - HL

Hui-Ying Luk

Assistant Professor

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, Texas, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

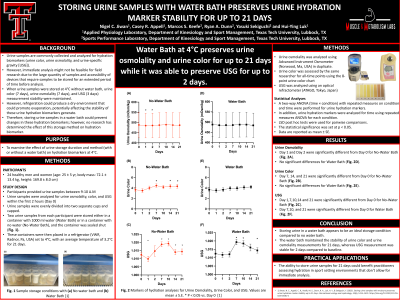

Urine samples are commonly collected and analyzed for hydration biomarkers (urine color, urine osmolality, and urine-specific gravity [USG]). However, immediate analysis might not be feasible for field research due to the large quantity of samples and accessibility of devices that require samples to be stored for an extended period of time before analysis. When urine samples were stored at 4°C without water bath, urine color (7 days), urine osmolality (7 days), and USG (3 days) measurement stability were maintained. However, refrigeration could produce a dry environment that could promote evaporation, potentially affecting the stability of these urine hydration biomarkers. Therefore, storing urine samples in a water bath could prevent changes in these hydration biomarkers.

Purpose: To examine the effect of urine storage duration and method (with or without a water bath) on hydration biomarkers.

Methods: 24 healthy men and women (age: 25 ± 5 yr, body mass: 72.1 ± 13.4 kg, height: 169.8 ± 8.0 cm) provided urine samples between 9 – 10 A.M. The baseline (day [D] 0) urine color (8-point urine color chart), urine osmolality (Advanced Instrument Osmometer), and USG (optical refractometer) were analyzed within 2 hours of the sample collection. Then, each well-mixed urine sample was divided into two urine cups and placed in a storage container with or without a water bath at 3°C. On D1, D2, D7, D10, D14, and D21, refrigerated vortexed urine samples were measured in duplicate for urine color, urine osmolality, and USG. The same researcher performed all measurements. A one-way ANOVA was performed for each variable and condition, followed by least significant difference (LSD) tests to examine differences. Data are reported as mean ± SE with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Results: When urine samples were stored in a water bath, urine color (p = 0.126) and urine osmolality (p = 0.053) were stable until D21, while USG was stable until D2 (p = 0.394). When urine samples were stored in no water bath, urine color (p = 0.005) was not stable at D7, while urine osmolality (p = 0.015) and USG (p = 0.005) were not stable at D1. For urine color in no water bath, D0 (3 ± 0) was significantly less than D7 (5 ± 0), D14 (4 ± 0), and D21 (4 ± 0). For urine osmolality in no water bath, D0 (487.9 ± 60.3 mOsm/kg) was significantly greater than D1 (484.6 ± 60.4 mOsm/kg). For USG in no water bath, D0 (1.012 ± 0.002) was significantly greater than D1 (1.010 ± 0.002) and was significantly less than D7 (1.019 ± 0.002), D10 (1.019 ± 0.002), D14 (1.014 ± 0.002), and D21 (1.014 ± 0.002).

Conclusion: Storing urine in a water bath appears to be an ideal storage condition compared to no water bath. The water bath maintained the stability of urine color and urine osmolality measurements for 21 days, whereas USG measurement was stable for 2 days compared to baseline. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: The ability to store urine samples for 21 days could benefit practitioners assessing hydration in sport setting environments that don't allow for immediate analysis. These findings will enable practitioners to perform multiple urine analyses within a given day, thus saving practitioners time.

Acknowledgements: None