Speed/Power Development

(50) POSITIONAL COMPARISON OF TIME TO TAKEOFF FOR COLLEGIATE MALE LACROSSE ATHLETES DURING HEX-BAR JUMP SQUATS

Justin R. Kilian, MEd, PhD, CSCS*D

Associate Professor of Exercise Science

Liberty University

Lynchburg, Virginia, United States- TC

Trace Cruz

Master's candidate

Liberty University

Lynchburg, Virginia, United States

Jessi Glauser, MS, CSCS*D, EP-C, USAW

Assistant Professor of Exercise Science

Liberty University

Lynchburg, Virginia, United States- DW

Daisy Wedge

Master's candidate

Liberty University

Lynchburg, Virginia, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Time to takeoff (TTT) is a measurement that quantifies the duration of ground contact in an explosive movement. Often used in body weight movements, TTT portrays the summation of times in each of the phases in jump assessments from the initiation of the jump until the athlete leaves the ground. A more powerful athlete is created if optimal force is held constant, and TTT can be reduced. If this performance aspect can be captured in testing, the data can be applied as a part of a comprehensive athlete profile.

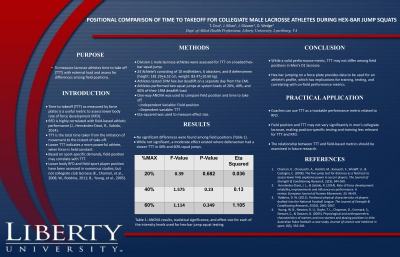

Purpose: This study aimed to assess male collegiate club lacrosse athletes' TTT to determine differences among positions.

Methods: Twenty-four college-age males (height: 181.29+6.52 cm, weight: 83.47+10.60 kg) performed loaded trap bar jumps with maximal intent at 20, 40, and 60% of their measured one-repetition maximum for the hex bar deadlift, which was measured on a separate day (188.10+31.54 kg). Ten midfielders, six attackers, and eight defensemen performed two vertical jumps at each load on Hawkin Dynamics force plates (Hawkin Dynamics Inc., Maine, USA). Each jump was separated by two minutes of recovery. A one-way analysis of variance was run, with the independent variable being positions and the dependent variable being TTT. Eta-squared effect sizes were also calculated to evaluate practical meaningfulness.

Results: No significant differences were found among positions for 20% (F(2, 21)=0.390, p=0.682, η2=0.036), 40% (F(2, 21)=1.575, p=0.230, η2=0.130), or 60% (F(2, 21)=1.114, p=0.349, η2=0.105).

Conclusions: In men's club lacrosse athletes, the TTT profiles were similar among positions. Despite no statistical differences, there was a moderate effect where defensemen tended to have slower TTT in 40% and 60% conditions. The in-game demands for lacrosse are high speed with frequent changes of direction that require short ground contact while expressing maximal force production for both offensive and defensive athletes. In addition to other metrics, TTT can be a valuable part of an athlete's performance profile, but the requirements do not appear to be different among positions for male collegiate lacrosse athletes. PRACTICAL APPLICATION: Strength and conditioning coaches can use TTT as a metric that provides one aspect of the time-force characteristics of athletes. These data could be used as a baseline metric to track progress over time when power is the primary goal. However, position-specific benchmarks do not appear to be necessary for lacrosse. Future research should focus on finding relationships between TTT and on-field performance metrics related to speed and agility testing.

Acknowledgements: None