Resistance Training/Periodization

(1) EFFECT OF AN ISOINERTIAL POST-ACTIVATION POTENTIATION PROTOCOL ON COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP KINETICS

Adam A. Burke, MSc,CSCS (he/him/his)

PhD Student

George Mason University

Gaithersburg, Maryland, United States

Meghan Magee, PhD, CSCS

Graduate Student

George Mason University

Centreville, Virginia, United States

Margaret Jones

Professor

George Mason University

Fairfax, Virginia, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Background: Acute bouts of isoinertial training can enhance muscle force production during subsequent plyometric exercise. Evidence supports flywheel isoinertial half squats as an effective lower-body preload activity. However, further research is necessary to determine the degree to which such post-activation potentiation (PAP) conditioning activities influence jump kinetics.

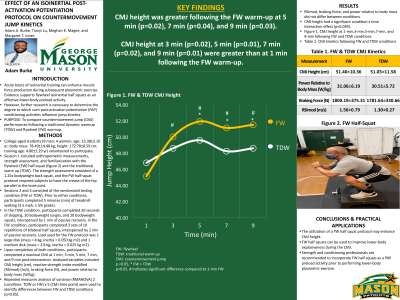

Purpose: To compare countermovement jump (CMJ) performances following a traditional dynamic warmup (TDW) and flywheel (FW) warmup.

Methods: College-aged students (9 men; 4 women), with >2 years of resistance training experience, and the ability to complete a 1.25x body weight back-squat participated. The crossover design consisted of 3 sessions. Session 1 included anthropometric measurements, strength assessment, and familiarization with the FW half-squat. Sessions 2 and 3 consisted of the randomized testing condition (FW or TDW). Prior to FW and TDW conditions, participants completed 5 minutes (min) of treadmill walking (3.5 mph, 1.5% grade). In the TDW condition, participants completed 20 seconds of skipping, 20 bodyweight lunges, and 20 bodyweight squats, interspered by 1 min of passive recovery. In the FW condition, participants completed 3 sets of 10 repetitions of bilateral half squats, interspersed by 2 min of passive recovery. Load used for the FW protocol was 1 large disk (mass = 4 kg; inertia = 0.050 kg·m2) and 1 medium disk (mass = 2.8 kg; inertia = 0.025 kg·m2). Upon completion of FW or TDW, participants completed a maximal CMJ at 1 min, 3 min, 5 min, 7 min, and 9 min post-intervention. Analyzed variables included CMJ height (cm), reactive strength index modified (m/s), braking force (N), and power relative to body mass (W/kg). Statistical analyses included 2 (condition; TDW or FW) x 5 (CMJ time point) repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA). Significance was set a priori to p< 0.05. Bonferroni post hoc analysis was used to identify differences between conditions.

Results: Figure 1 includes performance outcomes for CMJ height. RSImod, braking force, and power relative to body mass did not differ between conditions. CMJ height had a significant condition x time interaction effect (p=0.039). Post-hoc analyses indicated that CMJ height was greater following the FW warm-up at 5 min (p=0.02), 7 min (p=0.04), and 9 min (p=0.03). There were significant time-effect differences in CMJ height across trails for the FW condition, but not for the TDW condition. Post-hoc analyses indicated that CMJ height at 3 min (p=0.02), 5 min (p=0.01), 7 min (p=0.02), and 9 min (p=0.01) were greater than at 1 min. Figure 1 includes performance outcomes for CMJ height.

Conclusions: The utilization of a FW half squat protocol may enhance CMJ height. Practical Applications: FW half squats can be used to improve lower-body explosiveness during the CMJ; therefore, it is recommended to incorporate them as a PAP preload activity, prior to performing lower-body plyometric exercise.

Acknowledgements: None